more REVIEWs from Double reed news

PRINCIPLES AND TECHNIQUES FOR OBOE REED ADJUSTMENT

Cheryl D Wefler

Spiral bound A4 booklet of 40 pages - $28

Available from:

Cascade Oboe Reeds

P.O. Box 50336 Eugene, Oregon 997405

Tel. 541.517.7488

Website: www.cascadeoboereeds.com.

Email: cascadeoboereeds@msn.com

Ever since the mid-sixties I have dabbled with longer scraped reeds attempting to find increased flexibility, a bigger dynamic range, and ease of blowing without sacrificing tone quality. I have had some reeds that achieved these goals but I usually reverted to the well-known British style as I grew disillusioned with my efforts. I think that if I had had this little book sooner in my life I would have wasted far less time, less cane and achieved much more success.

My attention to this book was drawn by American oboe colleagues who rate it highly as an exposition of a fresh approach to reed adjustment. It is a distillation of advice from a number of distinguished American oboists who have influenced the writer. These include Robert and Sarah Bloom, Robert Sprenkle, Dr. J William Denton, Allan Vogel, Ray Still and Humbert Lucarelli. I must say at the outset that the book deals mainly with the American style of reed but its principles are easily transferred to the scraping of any reed style.

The issues dealt with include “Gouging and Sorting” cane, “Shaping and Tying”, “Pre-scraping”, “Knife Technique” and by far the most comprehensive and possibly most interesting section that on “Evaluation and Adjustment”. There is also a section on High Altitude reeds.

This is not a learned treatise on a specific style in the mould of Karl Hentschel’s book published by Moeck,“Das Oboenrohr” but a hands-on book of well thought out and reasoned tips. Very much a ‘step by step’ and ‘how to’ method of describing the process of sculpting blank reeds into little marvels! The author proclaims a way of thinking which is refreshing. For example we are asked to consider freeing up the reed within the piece of cane not by applying the scrape but by sculpting the surface of the cane. “Rather like chiselling away a piece of marble to free up the artwork that exists in that rock.” Thinking in terms of imagery, balance and proportion rather than strict measurement.

She also explores a knife technique that is interesting in that different knife angles, both relative to the scrape direction and deviation from the vertical, she believes produce different tonal qualities in the reed.

Having tried these ideas for a few weeks, particularly the knife work suggestions, I think she may well be right. Different angles of the knife applied to sweet spots on the reed’s surface have indeed made differences both on long-scraped styles and shorter European styles. Possibly I was using unusually (for me) sharp knives – a Gregson and a Jende Knife from Taiwan – and this alone made the differences noticeable. No, I don’t think so! For me there is something new here. Although I do now realise that my knives must be much sharper at all times!

The Chapter on “Evaluation and Adjustment” is very helpful. The author considers in detail the problems relating to pitch, response, relative stability, wrong resistance and tone. Her main reed style of course is of the long-scrape variety but I have found many of her ideas transferable to shorter styles. It is really this aspect of reed finishing that has been the main purpose of the book from the outset. There are many books available on reed making but there is room for more exposition on the specific task of adjustment.

The style of writing is one of encouragement and confidence in its range of ideas. There are one or two typographical errors and misplaced apostrophes but these do not detract from the ideas and the friendly nature of the text. The accompanying illustrations that are the work of her son Benjamin are clear and explanatory. The author is hoping to publish a second edition with corrections and amplifications in time for the 2009 International Double Reed Society Congress in Birmingham. She tells me that she is coming to Europe on this occasion for the first time and I’m sure it would be good to quiz her face to face about her ideas.

Geoffrey Bridge

DOUBLE REED ACCESSORIES REVIEW

A viable alternative to Goldbeater’s skin?

Browsing the Internet for accessories that could be given as presents to the oboist who have everything, I stumbled across the answer to sealing an oboe reed without the use of skins or membranes. I was curious to try this method as it appeared to be nothing but a wax pencil.

As I’m sure all oboists will have wrestled with goldbeaters skin that’s thick and stubbornly refuses to stick to itself and has a propensity for unravelling when you least expect it. Struggled with plumbers tape – the fashionable way of curing leaky reeds at the moment it seems – as it irritatingly assumes a useless thread that then refuses to spread into a manageable band. Suffered the unpleasant gluey taste and feel of the brown, glued goldbeaters skin! Certainly I have tried all these methods of correcting the results of my poor cane shaping and tying on. So have we the answer in this new product? I sent for one.

The wax pencil duly arrived and with it a list of instructions for use. The idea behind the product is that melted wax runs into the join between the contacting surfaces of the reed from the binding to just below the tip around the heart area of the reed. In fact slightly more sealed length than goldbeater’s skin would normally give. The constituents of this wax are a trade secret but it is odourless, tasteless and presumably non toxic. Application is easy with a bit of practise. This is an odd procedure nevertheless relying as it does on the direct heat of a 100-watt tungsten light bulb. (Please let’s not think about carbon footprints!) The wax is melted on the bottom of the hot bulb until a small bead forms. The reed is then swiped in the wax down each side and after dipping in cold water is sealed. It works!!!

Reeds that I had thought were well tied were obviously not air tight and the result of an application of the wax was rather like having your oboe back from a good technician – the sound came to life with a bloom that hadn’t been there before. I was quite astonished as I had been very sceptical. I did repeat the experiment with several reeds and found the same result. The great advantage of this waxing is that if say you have inserted a plaque and destroyed the seal, then an application of the heat from the light bulb - which you are probably using as a reed lamp anyway - seals it up again. Another advantage is that after application the reed stays the same in response. It doesn’t need any adjustment to the scrape to compensate for the extra weight and restriction placed upon it by the application of a sealing membrane.

There are difficulties. Gazing into the light bulb and trying to see the bead of wax and the edge of your reed is not easy. I used dark glasses at first to observe my actions as the bright light dazzled me. I used a lower wattage of bulb but found the wax did not melt quickly enough. If you like reeds supported by goldbeaters skin I feel that the wax will help to seal the reed and it is so quick to apply that it could be part of the reed-making regime.

The product “Leak Geek™” is American and is fully described and can be bought on line for $9.95 at Crispin Creations. It will last probably for your life time. I have used one on very many reeds at the time of writing and still am using only the point of the pencil.

The Bassoon-a-Ruta

Also included in the package from David Crispin the inventor of the “Leak Geek™” were a couple of white silicone bungs of two different sizes. These were devices called a Bassoon-a-Ruta for me to try. I passed one on to BDRS member Aileen Taylor who is an experienced bassoonist and a professional scientist so I expected a reasoned critical appraisal of the device.

The bung fits into the bell of the bassoon to create an airtight seal and there are two sizes to accommodate different bell apertures. The larger size being best for Heckels and Puchners. Low B flat is fingered, air is drawn in through the reed and the player lifts the appropriate finger or presses the flick key to open a flooded tone hole or vent. The water is sucked back into the bore and drops down into the butt joint. Aileen has used it with great success but recommends that the vacuum is not renewed before taking the reed from the mouth otherwise there is a danger of afflatus sounds, sucking noises and sundry gurglings which are counter to the purpose of the device, silent water removal!

The other possible disadvantage might be that shy bassoonists do not wish to be seen inserting the bung into the end of the bell during a performance when on the concert platform.

The inventor is John Ruze an American bassoonist and the device is distributed by Crispin’s Creations. The price is $9.95 plus carriage. There is an eBay shop facility.

I believe that David Crispin, is looking for a European distributor for his creations.

Geoffrey Bridge

REVIEW OF ILLUMINATED PLAQUE FOR OBOE OR BASSOON REEDS

by Geoffrey Bridge

I have long wished for a method of lighting a reed from the inside so that the contours of each blade could be easily visible. Holding up a reed with the tip down against a light source has been the classic way to assess the scrape but it is only a very rough and ready method as both blades are illuminated and viewed simultaneously. It is tricky to decide which blade needs a scrape to achieve a balance of the blades so we resort to other methods of judging the contours. For instance by reflected light, examining under a magnifier or resorting to the good old dial gauge and feeler. With the dial gauge method we have a measure of the cane thickness but also the depression of the springing of the touch piece. When measurements are made and the scrape is uneven through our poor knife work sometimes the feeler blade is not on a flat place so giving a spurious result.

I think the best way to judge the blades is to illuminate them individually as the eye is remarkably good at determining small variations of light and dark. This little invention by Antti Pakkanen enables just that. It is made out of a strong polycarbonate with a metal clad moulding which holds a tiny powerful LED light. The light intensity is adjustable from very bright to dim so one can choose the brightness appropriate to the density of the cane. The plaque fits between the reed blades as normal and the light shows up the darker areas where the cane is thickest and the bright areas where the cane is thinnest and all the gradations between.

I found in use that the reed must not be too wet or the water droplets show very dark in the scheme of things. After many weeks of use I can thoroughly recommend this plaque.

I had to change my way of working from scraping under an illuminated magnifying lamp, which of course ruins the effect of the interior light, to using the plaque exclusively for all my final attempts to balance the reed blades. I now use the magnifier without the light. It is far easier to balance the blades with this method providing that the scraping knife is sharp!

Are there any disadvantages? Well a couple or so.

There is a hot spot at the tip of the transparent sculptured plaque, which can be distracting, but as it is way down the back of the reed it is not a problem except for very long scrapes. It is also quite a lot heavier than the normal wood or metal plaque and the balance feels strange at first. Also I did find the adjustment of the intensity of the light a little difficult until I became accustomed to the operation of the pressure switch. However a major disadvantage for some may probably be the price. It costs around $120 not including shipping, from American suppliers and direct from Antti Pakkanen, the maker in Finland, €98 with free shipping at the time of writing. That is about £68 in our money! My sample was sent in a neat wooden case with several plastic oboe plaques as a bonus.

The light source is a Photon Freedom LED Torch sourced from America. The battery is easily changed when required. This tiny torch can be removed and used in many different and unusual ways! See Photon’s website.

Contact details are:

AP Double Reed

Antti Pakkanen

Itätullinkatu 26 A

28100 Pori, Finland

+358 2 633 0239

+358 44 522 3107

OBOE ART & METHOD Martin Shuring

Martin Shuring is Associate Professor of Music (Oboe) at Arizona State University. He has held orchestral positions in Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, the Florida Orchestra and the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra. He has edited Barret’s Complete Oboe Method.

Oxford University Press £15.00 in paperback. (224 pages)

ISBN 978-0-19-537457-5

This is probably the most important book on the practical craft of oboe playing that has been written in the English language in the past 50 years.

The first book that described the practicalities of oboe playing I remember was Evelyn Rothwell’s little volume that was published in the early 1950’s. This was followed by a more comprehensive version of her teaching thoughts in the three volume series produced in the late 1970’s, “The Oboist’s Companion”. Earlier in 1961 was published the then oboists’ Bible, “The Art of Oboe Playing” by Sprenkle and Ledet which gave a full and worthy description of the American oboe reed style. In 1977 Léon Goossens’ collaboration with Edwin Roxburgh produced a valuable addition to the learning and dealt in some detail with both baroque and contemporary practice. I feel though that “The Oboe, Art & Method” perhaps surpasses all of the above in its delivery of practical common sense teaching.

Since this time there have been comprehensive books written about the history of the instrument and advanced playing techniques. In this volume these aspects are dealt with when apposite but not in huge detail. Instead Martin Shuring has concentrated on describing a method of learning that could almost remove the need for a teacher. But not quite!

The book is divided into four main sections:

Fundamentals,

Reed Making,

Equipment and its Care,

Professional and Performance Considerations.

In Fundamentals he deals with posture, breathing and support, embouchure, fingers, articulation, expression, practice. In Reed Making he discusses construction, evaluation and adjustment – mainly applied to the American reed style. In Equipment, the selection of an instrument its care and adjustment are discussed in great detail. In Professional and Performance Considerations he is extremely helpful with aspects of deportment, behaviour and gives sound advice on career development.

In three Appendices he discusses thoughts for the complete beginner, gives fingering charts for both oboe and cor anglais and a complete trill-fingering chart.

The book is written largely in the first and second person for the sake of clarity of instruction. He attempts to ease the burden of the difficulties of playing the oboe so that it can sing and speak effortlessly. In order to do this he teaches that the basic simple things are done well. “Learn these right the first time and then move on to the next one,” he writes. “Everything musical I have ever heard or seen or learned is in some way contained in this book.”

There are so many interesting thoughts and ideas in this book that no oboe player should be without it. It is particularly valuable in confirming ideas we already might have but I can almost guarantee that however experienced the reader they will find something to think about anew. Even if it is only for the benefit of those who like to wear strong perfumes in the orchestral oboe section and read how Professor Shuring thinks this might not be the best idea for everybody else within smelling distance!

Geoffrey Bridge

No More Blocked Octaves for Oboists!

I first came across these octave box inserts at IDRS 2009 in Birmingham. These clever bits of gadgetry were said to prevent water gathering in the octave pipes. Something that oboists the world over have experienced from time to time, often wrongly described as ‘water in the octave keys’! The propensity for this phenomenon seems to depend on the individual instrument, the climate, the amount of warm-up and not least the courage of the player to take them out and clean them once in a while. I have loads of other theories, too: the type of reed we use for example, and how easily it vibrates in proportion to the amount of air we blow through. The more air we blow through the oboe the bigger the volume of water vapour whizzing past those little metal devices that we need to break the standing waves into their harmonics. More water is then likely to collect in the very narrow diameter octave pipes.

Having communicated with Professor Alberto Castellani, the oboist-inventor, via his website I received a set of the anti- condense octave boxes. These comprise a beautifully turned conical octave pipe and its receiver box, and a key to remove and replace the pipe as the top finish is a hexagon. This is much easier to manage than the usual two indentations in the top plate requiring a twin-pointed remover, anyone who has sheared off the top plate will testify! There are two ways of gaining benefit from this device; either the inserted pipe replaces the existing one, or alternatively an oboe technician can fit the complete assembly. This first option is relatively user-friendly, but it does require skill in re-corking the octave keys, as the height of the new pipe is greater and therefore the angle the cork pad makes with its mating surface has to be well judged. However, I decided to opt for the latter option so I hastened down to Edinburgh where my nearest technician Andrew May works and presented him with the job. An hour later the oboe was ready for collection. Andrew had had to remove a small portion of the wood of the oboe to allow the box to fit, as it has a small cylinder protruding into the walls of the bore and the existing diameter was about 1mm too small (see right).

Testing over a period of months proved very interesting. The most obvious advantage was a feeling of confidence. So this was a psychological benefit. The unexpected advantage was the improvement in the upper notes. When I had the boxes fitted to a Buffet Greenline oboe, on which the second octave notes have never entirely satisfied me, there was a subtle change in the quality of the sound. These notes had been good and stable but a little lacking in character compared to other oboes I own as perhaps now more open and vibrant, and I have heard this comment expressed by other users. What causes this effect is maybe something of the black arts! The pipes I have installed in the Greenline oboe are of the brass variety. There are other materials to be had and some may argue that the plastic inserts might be better against condensation; but how this would affect tonal qualities I am unable to say, as I have not tested those.

Returning to the main issue, do they work? In a word, yes – but with a little caution. Having spent many months playing in mixed climate and temperatures I have to admit that I will not be changing back to the original octave boxes. But I did have one embarrassing moment in an orchestra recently: having recommended these boxes to my colleague I was for the very first time suddenly losing the first octave notes to... water! The cigarette paper was absolutely flooded and I could not stop it!

Water collects in the receiving box under the pipe and is not easy to remove by sharp blowing across the hole. Stopping off the end of the top joint with a finger, closing the holes and sucking the water into the bore helps a little but the water soon collected again. The only cure was to dry out the oboe and blow through the individual octaves, collecting the water on a cigarette paper as normal. I persevered and the same thing happened to the second octave box some days later. When this whole experience happened again a few days later I took the pipes out of the boxes and cleaned them thoroughly with spirit, applied a little Vaseline to the holes before re-assembling. The sealing is easily achieved with the integral plastic washer but I still greased this to help make it airtight. (Waxing-in is probably not necessary.) Since then I have had no problems at all in hours of playing.

The moral in this episode is that cleaning is necessary from time to time; keeping the corks open with a cigarette paper at the very least – as Alberto himself suggests – so that the pipes dry between playing sessions, is also a help.

I have no hesitation in recommending that this invention is well worth having. I have heard argument that the octave box water problem can never be solved but this clever bit of beautiful engineering goes a long way towards that goal.

Signor Castellani can be contacted through his website: www.oboicastellani.it or on Tel/Fax: +39 (0)55 89 54 538 His daughter acts as his trusty translator.

Geoffrey Bridge August 2011

A Fossati Experience

For a number of years now I have been interested to try the Fossati range of oboes. Apart from a very quick blow at one of the British Double Reed Society’s Conventions I have never had any experience with this maker’s instruments. Thanks to the enthusiasm of Johan Bricout their director of sales for a review, three oboes arrived recently for me to keep for a few weeks trial. The models sent for review being:

The Fossati MB oboe

The Fossati Soloist V oboe

The Tiery E40 - the top of the range student oboe

The Company

Gérard Fossati who had worked for the Rigoutat Company founded the company in 1983. The manufacturing base was set up in Montargis a city 110 kilometers south of Paris in the heart of the region known as the Gâtinais. There is also a subsidiary workshop and sale room in Paris near to the National Conservatoire of Music. At the outset in 1983 Gérard was enthusiastic to use the latest CAD (Computer Assisted Design) technology in developing the design of his oboes. He was also keen to work with oboists throughout the world to develop ideas from many different playing styles. The Company prospered and sold a range of oboes, d’amores and cors anglais throughout the world in what is a highly competitive market. In 2009 M.Fossati retired and the company was bought back by four employees. Daniele Lefevre who is now the President, Stéphane Guillaume the head technician, M. Emery and M. Braun.

Developing the Design

Since the buy out, in order to improve the professional range Stéphane Guillaume sought opinions and play-testing from players such as Michel Benet from Orchestre de Paris, Tomoharu Yoshida from NHK in Tokyo and Hitoshi Wakui from the WDR Radio orchestra in Cologne. Two different designs of professional oboe are now in production, the new Soloist V and the MB oboe that replaces the limited edition Anniversary Oboe in the catalogue.

The traditional Soloist Model has also been discontinued.

The two designs are equal in status but have a different feel to the way they blow. Instead of designing an oboe to produce a specific sound the aim with these designs is to produce a different feel to the way the each oboe blows whilst still meeting the tonal requirements of the modern orchestral and solo player. It was therefore very interesting to have these instruments in my possession for a while to discover how well these aims had been achieved.

The Oboes

The first thing that strikes one nowadays with all the best modern manufacturers of professional oboes is the excellent way their instruments are presented. The cases are well made and fit the instruments snugly, they are attractive and practical and almost all use a cover, often sheepskin-lined, to add further protection. Fossati are no exception in this and use the typical “French-style” case with fur-lined cover. They also transport their oboes with each joint secure in a plastic bag and recommend that in the early days of blowing-in that the joints are replaced in these after playing to allow for a more gradual cool down period. This takes me back to the first Rigoutat I bought that had its top joint wrapped in a piece of bright orange/silver plastic survival blanket that I was asked to use for the first three months of blowing-in! This caused much merriment in the wind sections I was in at the time.

My initially impression with the instruments was that they are a high quality product. The finish is exemplary with Palladium plating on both the professional models and silver-plating on the student model. Palladium plating resists tarnish much better than silver for some players. The key work is well made and has quite a delicate feel as the dimensions of some keys, in particular the left hand little finger cluster, are slightly smaller than other makers’ oboes. The springing is very light and well balanced and the heights of adjacent plates and keys well judged. This shows that the finishing of the instruments is carefully carried out. This stage is so important and some manufacturers in the past have fallen short of perfection in their haste to meet a high demand. This final manufacturing stage takes time, knowledge, patience and skill.

The three oboes were equipped with a thumb plate mechanism that showed thoughtful design in that the plate sloped very gently toward the first octave key. The third octave key is carefully shaped and easily accessible from the thumb plate. Importantly it doesn’t hamper the action of the thumb by becoming inadvertently involved! It has an adjustment screw built in.

One Trill Key System

Gerard Fossati had instigated several innovations in his time with the company, amongst these was a single hole for the C/D, C/C# trills known as the One-trill system. In recent tests with many oboists, not all Fossati players, Head of Design Stéphane Guillaume made two prototypes with the same bore, one with the One-trill key system and the other with the standard Two-key system. Oboists preferred the former.

After acoustic research it appears that the extra volume of the two holes cut into the bore affected playing flexibility with regard to reed types. The single hole is a preventive measure minimising the risk of cracking but it makes the oboe with its narrow bore less flexible. D’amores and cors anglais with their bigger bores retain the single hole but the current oboe range has reverted to the double trill hole with a wider distance between them as in Rigoutat designs. (See accompanying photos)

Left Hand Reversed Adjustment - another innovation.

The G and A plates of the left hand close the B flat and C keys by direct action. This allows for an adjustment screw on the G key stop that enables the intonation of the A to be adjusted. The more traditional arrangement has the lever pushing upwards on a bar and this can result in a sloppy key action. See the accompanying photographs comparing the Fossati system with a traditional Buffet Greenline.

Fossati MB (Michel Benet) Oboe

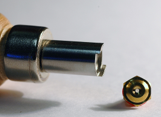

The MB oboe was the first of the three that I played. For all the initial play-tests I used a standard shallow U-scraped reed with a medium width shape - an RC 13 straight shape from Roseau Chantant - fitted to a Reeds n Stuff shaping machine. The staple I used was a new interchangeable design from Chiarugi that fits a Loree mandrel and has four different lengths of tube that can be unscrewed to give staple lengths of 45, 46, 47 and 48mm. This was useful for maintaining pitch using the same reed if I had to compensate for any pitch differences between oboe models.

(See photograph)

I think it perhaps useful to describe how the two professional oboes feel by comparing them like for like. The MB is the marginally the heaviest of the oboes. The walls appear to be slightly thicker and the bell is heavier than the Soloist V bell by about 8 grams. The upper part of the top joint is shaped to give more wood around the reed well. The resultant tone quality is heavier than the Soloist V and has more resistance in the blowing. The high notes were not as easily “pinged” out, that is until I became accustomed to the way the oboe blew. I was extremely impressed by the ease that the lower register played. The tone holes of both instruments’ bottom three notes are quite large compared to other oboes I own, which may or may not be a factor, and the sound is open and resonant despite needing good support. Controlling this instrument is easy and the slight resistance to blowing gives confidence that the sound will not break up and become sharp and ragged.

Both oboes are very smooth over the break between the middle C and D. A good test being the first notes of the second movement of Bach Double Concerto in the D minor version with the drop to low E after the D being critical. These oboes passed with flying colours, the low E being safe, rounded and resonant.

Soloist V

Fossati MB top joint

Fossati MB Bell

This instrument has the normal reed-well shape and features gold pillars, reed socket and tenon banding to cosmetically enhance its appearance. Both instruments incidentally have metal-lined tenons, which really helps the security of the coincidences between top and bottom joints. The alignment of these is accurately adjusted and again testament to the fine finishing these instruments have been given prior to delivery.

I found that this oboe played very easily and I was anxious that it wasn’t just too easy for comfort. So often this type of easy-blown oboe has flying Fs and unstable second octave As - but has easy harmonics, multi-phonics and extreme high notes. Often this is a result of a worn bore!

This one was very well behaved. The high notes were clean and free sounding without any suggestion of under harmonics. This means that the venting has been well thought through. The first finger left hand plate, sporting a round venting hole and not the more common diamond shape, had the middle range of D, D# and C# playing without any problem.

The Philly D worked well on both these oboes but I have never been totally convinced that this makes life easier. Oboes without it play G to top D just as easily or with just as much difficulty - so much depends on the reed!

The scale on both oboes is even with very good tonal stability throughout the range. No flying Fs, stable top As, the extreme notes up to highest A as easy as any on oboe I own and easier than some. The Soloiste model being preferred with my reed set up for the latter.

I experimented with some different reed types from wide shapes such as RC15 to the old and quite narrow Michel 7.2 and a very narrow Hörtnagel shape. I also tried reeds made on different staples and the oboes reacted well to these changes. The bigger volume staples tended to make the middle B and C a little sharper than the slightly smaller Loree style.

Tiery E40

This oboe is the top of the range student oboe and sells for a very competitive price. This model has a thumb plate installed and a third octave key neatly placed to its left and out of the way. Fossati offer an almost complete standard Gillet system with fewer adjustment screws than the professional models.

The inherent sound quality is bright and easily produced but on listening to recordings that I made it is plain that there is not quite the sophistication in its presentation as the professional models. To make the best sound would need a slightly different reed set-up with perhaps a little more resistance. There is a certain “glow” in the sound but brashness creeps in with my usual reeds. The ease of blowing, the lightness in weight and the full system make this a strong contender amongst the excellent intermediate oboes available.

Conclusions

I was delighted to have these oboes in my company over the Christmas period and was able to give them a good play test. I was very impressed by the high quality of finish of these instruments, particularly of the professional range. A really well buffed jewel finish reminiscent of the Loree brand.

There is a family resemblance in the sound with all makers and there is no exception here. I would place the sound in the makers’ spectrum about mid way between the brighter Lorees through to the darker Marigaux M2.

Considering the professional models the sound is vibrant yet full and warm most particularly with the MB model. The Soloiste V is a little more open and free blowing and was much like my Rigoutat in its tonal envelope. The projection of them both is excellent and they can make big controllable sounds and still be decent!

My thanks go to Johan Bricout for this opportunity to try these oboes and I was very reluctant to pack them up and see them leave the premises. I had my favourite but it would be churlish to name “her”.

Geoffrey Bridge 2012

See next page for comment on

Ramon Ortega Quero’s Luzern Festival recital 2010.